S4 E6: What’s the buzz about "Murder Hornets"?

- Greg

- Dec 15, 2023

- 13 min read

Hello Everyone,

You may have seen the news or maybe read where they mention an invasion of “Murder Hornets” coming to wipe out the bees and other insects in the UK.

I would love to say this is all sensationalised nonsense designed to make people buy more newspapers etc … Sadly, it’s not a huge leap from the truth.

Asian Hornets (Vespa velutina) have rapidly travelled all the way from Southeast Asia to Europe and have been causing absolute mayhem on mainland Europe since 2004. France was the first European country to suffer from the Asian Hornet, when a hibernating queen was unknowingly transported there with some goods for sale. Since then, the threat has spread outwards to surrounding countries like Spain and Portugal and they are all having a particularly bad time of it now. A positive, if it can be called one, is that these examples of invasions can be used as a way of looking into the future of beekeeping if the hornets gain a foothold here in the UK.

The invasion of Asian Hornets in the UK can be attributed to several factors, both natural dispersal and human-mediated transport. Mated queens emerge from hibernation in the spring and disperse to find suitable nesting sites. They can travel significant distances, establishing colonies once they find a suitable location. Fortunately, the shortest distance across the English Channel is around 20 miles which is much further than a mated queen can fly. Unfortunately, these hornets can accidentally be transported to the UK through imported goods or vehicles. This unintentional introduction poses a significant risk to the UK's ecosystem and biodiversity, as the hornets can adapt quickly and establish colonies.

Here is a link to a bee farmer in Brittany and what an Asian Hornet attack looks like:

Although we have been safe from significant incursions for quite a while, mostly thanks to us living on an island, the hornets have had enough time to build up numbers across the pond and have made some real gains this year. The National Bee Unit have reportedly destroyed 54 Asian Hornet nests all over the UK so far. Even more worryingly, there have been some sightings as far north as York, which scientists thought would be too cold for them to survive! It only takes one successful hornet nest to produce around 350 Gynes (Virgin Queens) for the following year! Granted, these Gynes will need to mate and survive our harsh damp winters but seeing how well they have adapted to the rest of Europe, the chance for expansion is still an almost certainty. Scary stuff…

We do have a native species of hornet already in the UK called the “European Hornet” (original I know…). In essence the European Hornet is very similar to our common wasps in life cycle and temperament. The main differences are that Hornets are considerably larger than their wasp cousins with their workers reaching around a whopping 2.5cm-4cm in size whereas wasps are only around 1.2cm-1.7cm long, and wasps are way more common than Hornets. Generally, if its black, yellow and doesn’t have much in the way of hair, it’s probably a common wasp, if you see a “massive wasp” then chances are it was a European Hornet.

So, the question is, “if we already have hornets, why is this new variant such a big deal?”

Well dear reader that is an excellent question, well done, also might I add that your hair looks tremendous today. Our European Hornets (Vespa crabro) have a large and varied diet and hunt all manner of insects such as grasshoppers, flies, wasps, dragonflies etc. tending not to cause much of an issue to our wildlife, as they don’t specifically target any one type of insect.

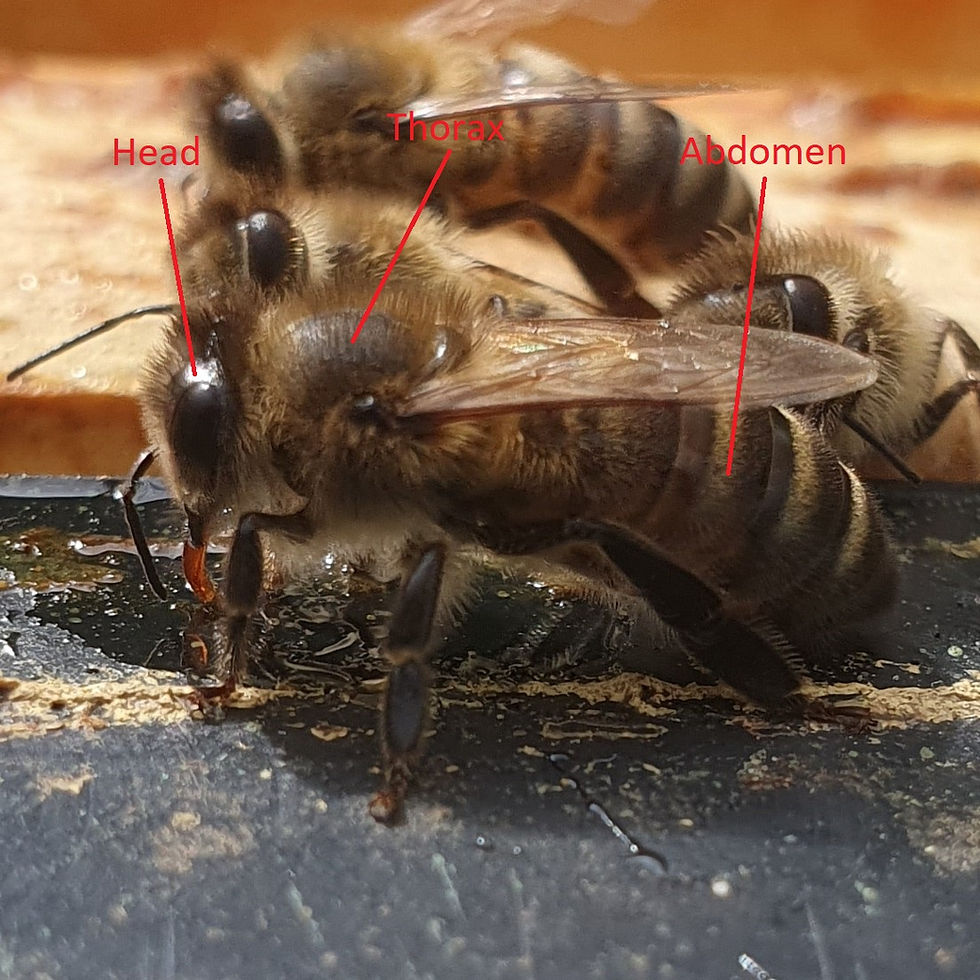

Asian Hornets on the other hand are specifically designed to attack Honeybee and Wasp nests. They do something called “hawking” where they hover around the hive entrance and, relying primarily on visual cues, wait for a forager to attempt to land. When a honeybee is within striking distance, the hornet captures it in mid-air, immobilizes it chewing away everything apart from the thorax, and swiftly carries it back to their nest. Asian Hornets are skilled hunters, capable of capturing multiple honeybees during a single foraging trip if they so wish.

This predation can result in significant losses for honeybee colonies. As a result, honeybees are forced to defend their hives, but this defence mechanism is often insufficient against the relentless onslaught of Asian Hornets. Once a hive is weak enough the hornets make their way inside and massacre the rest of the inhabitants. It's really brutal and can wipe out even the strongest colony in a matter of weeks and that is why they are so dangerous as an invasive species. Usually, a strong colony of honeybees can fend off wasps and other interlopers without much in the way of negative effects. The guard bees at the hive entrance go all King Leonidas at the Battle of Thermopylae and keep the invaders out, whilst allowing the forager bees in and out.

The Asian Hornet’s Hawking method weakens the hive significantly without the guard bees even coming into the fray. The honeybee foragers are specifically targeted, meaning the colony slowly starts to starve as the numbers dwindle, significantly weakening the guards before the final push. It’s a siege that Caesar at Alesia would be proud of! Hmm maybe that was too many ancient history comparisons…

European Hornets (Vespa crabro) and Asian Hornets (Vespa velutina) share some similarities in that they are both Hornets and are meat eaters, but also have notable differences. In terms of size, European Hornets are generally larger, with queens reaching up to 35 mm in length, while Asian Hornet queens are around 25 mm in length.

Appearance and hunting tactics are the biggest difference though. Asian Hornets have dark brown or black bodies with a yellow or orange face, featuring a single yellow band on the abdomen towards the rear. Asian Hornets are also known as "Yellow-legged Hornets," due to their (you guessed it!) bright yellow legs which no other hornet species has. European Hornets, on the other hand, have more orange and yellow markings on their abdomen, thorax, and head, similar to that of our common wasp.

The Asian Hornet’s life cycle is quite similar to other wasps and hornets with their numbers slowly building to a crescendo in summer when they reproduce and then start dying off. There is one defining difference though, let's see if you can spot it. Here is a summary of their yearly cycle:

Winter (December to February):

During the winter months, the only surviving individuals are the newly mated queen hornets, which overwinter in protected locations such as hollow trees, attics, or other sheltered spots. This is when queens are accidentally transported to new areas such as if a queen hides in a cardboard box or within some logs set for delivery in a different country.

Early Spring (March to April):

As temperatures rise in the spring, the mated queens become active and search for suitable nest sites. They can travel miles from their wintering spot, snacking on early sprouting flowers for energy.

The queen constructs a small nest out of wood fibre resembling a paper umbrella and lays the first eggs, which quickly develop into workers.

Worker hornets emerge from their cells and immediately begin foraging for food, primarily hunting for insects to feed the developing larvae.

Late Spring (May to June):

The colony grows as more workers are produced, and the nest expands in size.

Asian Hornets become more numerous and pose a greater threat to honeybee colonies during this period.

Summer (July to August):

The colony reaches its peak size during the summer months, with a substantial number of workers.

Asian Hornets are most active in hunting and foraging for food, this is when there is a noticeable decline in honeybee colonies in the area.

The colony may produce new queens and males towards the end of this period.

Late Summer and Early Fall (September to October):

As the days get shorter and temperatures cool, the Asian Hornet colony prepares for reproduction.

New queens and males are produced, and mating occurs.

The mated queens seek out suitable locations to overwinter, while the rest of the colony begins to decline.

Establishment of Secondary Nests (September to October):

With the departure of the new queens, the primary colony begins to decline.

Some of the worker hornets from the primary colony may establish secondary nests, which are smaller and serve the specific purpose of rearing new queens and males.

Secondary nests are typically hidden in concealed locations, such as dense vegetation, tree hollows, or similar spots.

Continuation of Secondary Nest Activity (October to November):

The worker hornets in secondary nests produce and care for the developing queens and males.

The secondary nests will not persist for as long as the primary nest, as they serve a more limited purpose in the hornet life cycle.

Late Fall (November):

The colony continues to decline, and most of the workers and males die.

Only the newly mated queens survive and find sheltered spots for overwintering.

The life cycle of Asian Hornets easily adapts to their local climate and availability of resources, so the timing of these events can vary somewhat. However, the general pattern of colony growth, foraging, and reproduction remains relatively consistent from year to year.

Did you notice anything strange about the life cycle?

That’s right, they establish secondary nests!

Wasps and other hornet species stick to their main nest, and this is their base of operations until the original queen dies, and the rest of the colony dies off too. Groups of Asian Hornet workers break away and start their own little nests specifically designed to produce more queens and males. This is strange because most eusocial insects such as Honeybees, Wasps and European Hornets have a caste system where only a queen can produce fertilised eggs. Although workers are female, they lack the ability to mate and produce anything other than unfertilised eggs which can only produce males (drones). Asian Hornet workers can produce unfertilised eggs which can in fact turn into queens as if they are fertilised. It’s a process called “Thelytoky”.

Ticky tocky?..

Thelytoky is a type of asexual reproduction in which new queens are produced from unfertilized eggs. Queens produced this way are referred to as "clonal queens" as they have the exact genetics as the original queen. This process allows the Asian Hornet colony to generate additional queens for future colony foundation, even when the original primary (foundress) queen is not present in the secondary nest. It's important to note that thelytoky is a unique feature of certain hornet species, like the Asian Hornet, and it is not observed in all hornet species or social insects.

Remember how I said one colony can produce around 350 new queens for the following year? Now imagine that a lot of those queens are produced in these secondary nests that can be miles away from the original. You can see how just one successful nest can cause a whole heap of trouble for the country and our wildlife.

Something I find interesting about all this is that Honeybees exist in Southeast Asia where these hornets come from. Although they are obliterating many apiaries of Western Honeybees, the Asian Honeybee seems to be quite stable in numbers. This is because they have evolved with the Asian Hornet and have come up with a nifty trick to deal with them. This defence strategy is known as "heat balling" or "thermo-balling,", which you may have heard of before if you enjoy watching nature programs, and it involves the following steps:

Detection: When Asian honeybees detect the presence of an Asian Hornet near their colony, they collectively recognize the threat. Whereas Western Honeybee guard bees hang around the entrance waiting for trouble to come to them, Asian honeybee guards can be found flying around the entrance, patrolling, and looking for trouble.

Alarm pheromone: Some worker bees release an alarm pheromone to alert other bees in the colony. This pheromone signals that a hornet is nearby and mobilizes the bees for a coordinated defence. Both types of honeybees have alarm pheromones, but they have different effects. Western Honeybees will act agitated, defensive with their butts (and attached butt-daggers) in the air, and some will fly aggressively towards the smell of the pheromones and try to sting the subject of their ire. Once they sting the intruder the Western Honeybee will walk about or cling on as hard as they can to ensure their pheromones alert the others where the target is located. Asian honeybees on the other hand do something called “shimmering” when they smell the alarm pheromone. Shimmering involves the bees doing a synchronised vibrating which looks really impressive, like waves on a calm lake. This vibrating raises the temperature of the honeybees preparing them for what comes next.

Encirclement: The worker bees surround the hornet and form a tight cluster around it. They may create a ball or cluster of bees around the hornet, effectively trapping it. European bees can also form a cluster around a threat, but their cluster is disorganised, and each bee is trying to sting the intruder rather than working together.

Vibration and heating: The bees in the cluster generate heat by vibrating their flight muscles. This behaviour, known as thermogenesis, raises the temperature within the ball or cluster. The bees can increase the temperature to a level that is lethal to the hornet but not harmful to the honeybees themselves.

Suffocation and overheating: The heat generated within the ball suffocates the hornet and raises its body temperature to a lethal level, typically over 45°C (113°F). Hornets are not adapted to withstand these high temperatures, which causes them to die from overheating.

Disposal: Once the hornet is incapacitated or killed, the honeybees remove the dead hornet from the colony to free up the entrance and also so it's corpse doesn't attract more hornets.

It's important to note that this vibration defence mechanism is specific to Asian honeybees, such as Apis cerana, and is not used by the Western Honeybee (Apis mellifera) commonly kept in Western countries. Western Honeybees are more vulnerable to Asian Hornet predation because their inclination is to sting a threat and unfortunately a bee’s sting is less effective to an Asian Hornet than the Thermo-balling. Maybe in the future our Western Honeybee will learn this behaviour but, in the meantime, its best to try to prevent them from needing it in the first place.

“So, what can be done to slow the Asian Hornet invasion?” I hear you ask, whilst peering from behind the sofa… with your amazing hair... (seriously, is it a new conditioner or something?)

There are several strategies that can be implemented. First, public awareness and education are crucial, as this helps in early detection and reporting of invasive species, enabling rapid response. Efforts should be made to establish monitoring and reporting networks to track invasive species' presence and their impact. This can be achieved through citizen science initiatives and government agencies collaborating with experts and beekeepers.

Additionally, control measures for invasive species should be developed and implemented, which may include locating and destroying nests, trapping methods, and research into biological control strategies that can mitigate the spread of invasive species.

Finally, strict import controls can help prevent accidental introductions of invasive species, and research should be funded to better understand these invaders and develop effective management strategies. By combining these efforts, the invasion of harmful species can be slowed and mitigated, protecting local ecosystems and pollinators.

Fortunately, APHA (Animal and Plant Health Agency) are doing just that, but there’s no way that it can be successful without the general public helping out. Here is a link where you can download an app for your phone to notify the National Bee Unit if you think you may have seen an Asian Hornet: https://www.bbka.org.uk/faqs/report-a-sighting-of-the-asian-hornet

If Asian Hornets become established in the UK, it would have a series of cascading effects on the environment and various sectors. First and foremost, their predation on honeybees and other pollinators would disrupt local ecosystems. The decline in pollinators could lead to reduced crop yields, affecting agriculture and food production.

Furthermore, honey production would likely suffer, impacting the livelihoods of beekeepers. Additionally, the presence of Asian Hornets can lead to human health concerns, as their stings can be painful, especially for those who are allergic. The aggressive defence of their nests can pose a risk to people in affected areas.

You should see the gear exterminators have to wear to dismantle an asian hornet nest! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fBcsxnkL97k&ab_channel=WSDAgov

The invasion of Asian Hornets is already adding to the strain on resources, as authorities and organizations invest in control and eradication efforts. This includes the cost of locating and destroying nests, monitoring, and public awareness campaigns.

Ultimately, the establishment of Asian Hornets in the UK could have significant ecological, economic, and social consequences. Slowing their invasion and minimizing their impact is crucial to safeguard local ecosystems, agricultural practices, and human well-being.

The invasion of Asian Hornets underscores the need for vigilance, research, and proactive measures to protect honeybees and maintain the rich biodiversity of our landscapes. We must rise to the challenge and safeguard the delicate web of life that our buzzing friends are an integral part of.

I hope you are all safe and well,

Greg

Bonus question that I was just asked by a beekeeper I’m mentoring “why don’t we just import Asian Honeybees into the UK to combat the effect of the Asian Hornet?"

It’s a good question and they also have fantastic hair, not as good as yours though dear reader.

As mentioned above, Asian Honeybees have a pretty good defence against the Asian Hornet so it makes sense that they would stand a better chance of survival if the hornets became established in the UK. There are a few issues with this train of thought though; the importation of live honeybees, including Asian honeybees (Apis cerana), into the UK is heavily regulated to protect the country's native honeybee populations and the local ecosystem. The reasons for strict regulations and restrictions on importing honeybees are:

Disease, Pathogen and Pest Concerns: Imported honeybees can carry diseases, parasites, and pathogens that may not be present in the local honeybee population. Introducing new pathogens can lead to disease outbreaks among native honeybees, which can be devastating for both managed and wild colonies. Asian honeybees are unfortunately lousy with a type of mite called Tropilaelaps mites. These are very similar to Varroa Destructor (Varroa Mites), which we already have in our country, but have yet to get close to our shores. Tropilaelaps mites are not necessarily more dangerous than Varroa destructor mites; rather, both types of mites pose significant threats to honeybee colonies, and combined they could cause all manner of problems to our ecosystem. Its best to keep them out for as long as we can.

Competition with Native Species: Introducing non-native bee species, even if closely related, can lead to competition with native honeybees for forage resources, nesting sites, and habitat. This can impact local ecosystems and potentially harm our native pollinators.

Interbreeding and Hybridization: Introducing new bee species can lead to hybridization with native honeybee populations. Hybridization can alter the genetic makeup of native bees and potentially lead to reduced local adaptation and resilience and can sometimes have unknown consequences to the honeybee’s temperament.

Protecting Local Honeybee Health: Regulatory measures aim to protect the health and genetic diversity of local honeybee populations and prevent the introduction of pests and diseases that could harm bee colonies. Currently there is a group of hobbyist beekeepers and farmers under the group name “BIBBA” that are trying to breed back our native “Black Honeybee.” We have had so many years of importing German Buckfast, Italian Carniolan among other species from outside of the UK that our feral colonies are all mongrels of our native bee and these outsiders. It is thought that the Black Honeybee is best at dealing with our climates meaning less winter losses and more feral colonies flourishing in the wild.

Climate: Asian honeybees are not built to survive the UK climate. The UK has a temperate maritime climate with distinct seasons, including cold winters, which can be challenging for bee colonies. Asian honeybees are more suited to the tropical and subtropical climates found in their native range.

To protect honeybee populations, pollinators, and local ecosystems, most countries, including the UK, have strict regulations on the importation of live honeybees. Beekeepers and researchers interested in importing bees for specific purposes must adhere to these regulations, which often include quarantine, testing, and certification procedures to reduce the risks associated with bee imports. These regulations are in place to strike a balance between the need for genetic diversity in bee populations and the protection of local ecosystems and agriculture. The best thing we can do is prevent invasive species from coming to our island and if they do come here then try to protect our bees, feral and managed, as best as we can through trapping and removal of nests.

Comments